Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Brave designs

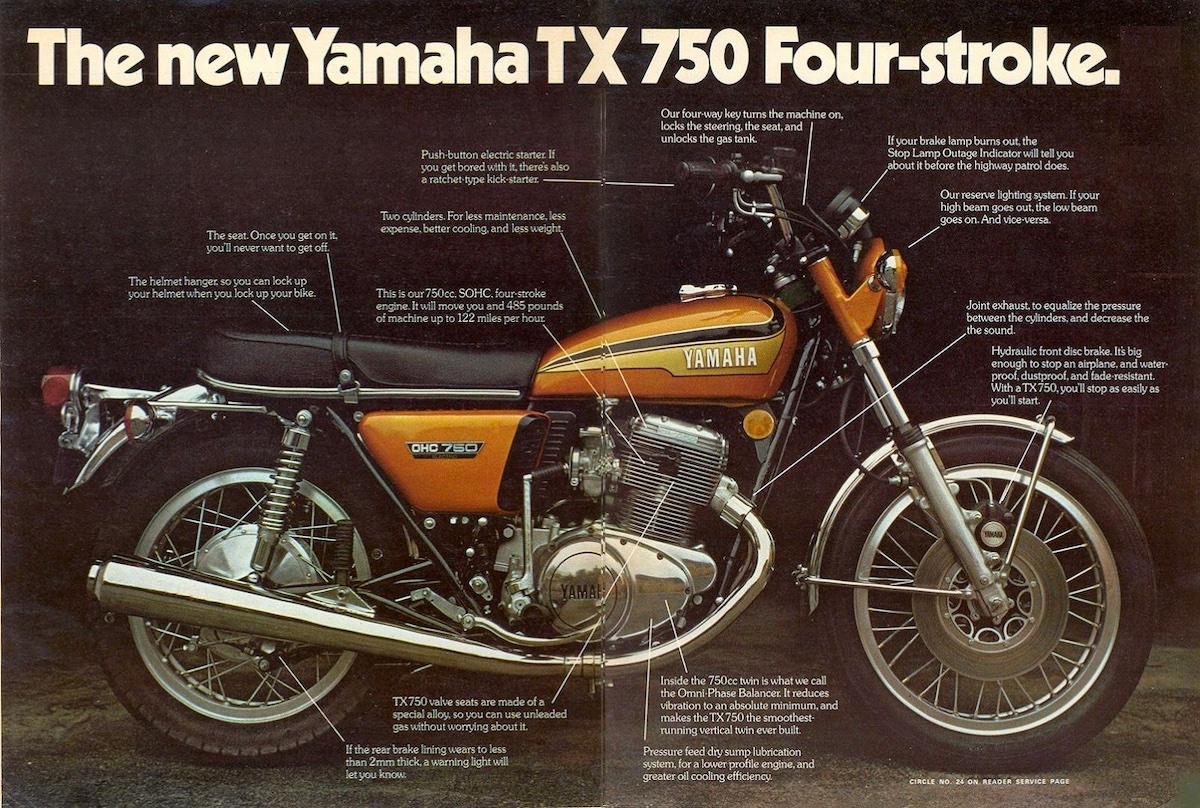

Yamaha TX750 – mini profile

(Guy 'Guido' Allen, June 2025)

Yamaha has a worthy

history of trying courageous designs that sometimes

struggle and the TX750 of 1972 counts as one of them

The mission – and perhaps the gamble – was at a time

when Honda and Kawasaki were getting into four-cylinder

four-strokes, Yamaha would refine the vertical twin into a

machine that offered an intriguing performance

alternative.

Yamaha at this stage had a foot in both the two- and four-stroke camps, but could see the latter would end up dominating.

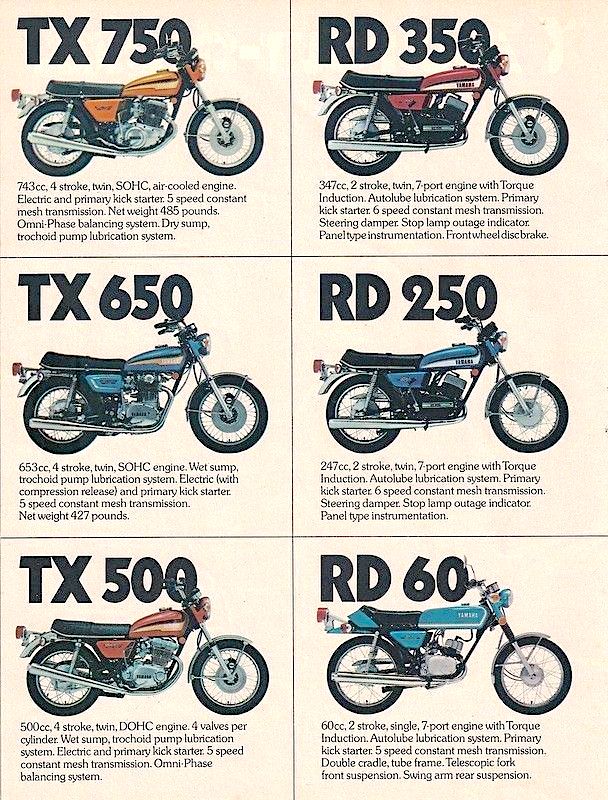

Where the XS650 (listed above as a TX650) was essentially

the company's interpretation of a tradition British twin,

with Triumph as the nearest target, this new-gen TX750 was

aimed at raising the stakes. In theory what you would get

is 63 horsepower (a respectable number for a twin at the

time) in a package that didn't punish the rider with the

let's say 'boisterous' vibration famously shared by the

XS650 and the Triumph Bonneville 750 twins.

(Just as an aside, one of my favourite memories of owning

a Yamaha XS2 was blipping the throttle as it stood warming

up on it's centrestand, and having to walk with it as it

scuttled across the concrete...)

Back to the TX. It was effectively a new machine with

some nice appointments. For example the front end allowed

for the fitment of a second disc brake, while the laced

wire wheel rims were aluminium rather than steel, made by

DID.

Where the company hoped to make a name was by taming the

notorious vibration caused by a large 360-degree parallel

twin. To this end, it fitted a two-stage balancing system

labelled the Omni-Phase. One set of weights were there to

counteract the inherent issues with a 360-degree crank

throw, while the second was to balance out the first set

of weights.

While good in theory and fine when tested in moderate

conditions, a combination of issues that likely included

an under-done pre-launch testing regime raised a cascading

set of issues on the track and on the road. In early

versions, the spring-loaded tensioner for the chain

connecting the balancers proved inadequate, throwing them

out of phase. With that addressed, the next issue was the

chain itself would stretch, also throwing the set-up out

of phase and introducing serious vibration issues. Plus

the balancers would cavitate the oil, compromising the

lubrication to the crankshaft and the engine would

overheat.

There were further areas to be addressed.

“Everyone wanted it to be the sophisticated Japanese

answer to the Triumph 750 but it was a service disaster,"

said Spannerman in a piece we did back in 2010 for

Motorcycle Trader magazine.

Troubles aside, the TX750 was well-regarded as a ride.

Cycle World in

the USA, in a 1972 review published at the start of 1973

noted: "Even though the multi-cylinder mania appears

to be taking over, there are many motorcyclists who know

and appreciate the relative mechanical simplicity of a

vertical twin, the smaller number of moving parts to wear

out and give trouble, and who just plain enjoy the aura of

riding a twin."

It went on to observe: "Ride smoothness is very good, but

this smoothness comes at the expense of inhibited

cornering characteristics. Front fork travel is good and

the forks themselves do a good job of soaking up the

bumps, but they are too soft for really precise steering

at high speeds in turns. The same goes for the rear units,

which exhibit too little rebound damping and make the

machine 'pogo' in fast, bumpy turns.

"The TX750 is really not a sporting rider’s machine like

most vertical twins, it’s a luxurious tourer."

Its mechanical issues spooked the market, particularly

given how serious they were. You were looking at a

crankshaft change when things went pineapple-shaped.

There were recalls, one of which involved fitting an oil

cooler and, during the 1972-74 production run, a

significant series of updates. In the end, the machines

could be made reliable though perhaps not under race

conditions.

With the wonders of more patience, gentler use and

better-funded owners, TX750s have found an international

niche market. We're aware of a few restored examples

getting around in Australia, while there is an international

online forum.

***

At auction

You don't often see them pop up for sale. Here's an

example from Bring a Trailer in the USA in 2022. It went for

Au$8100 (US$5300, GB£3900).

More info

***

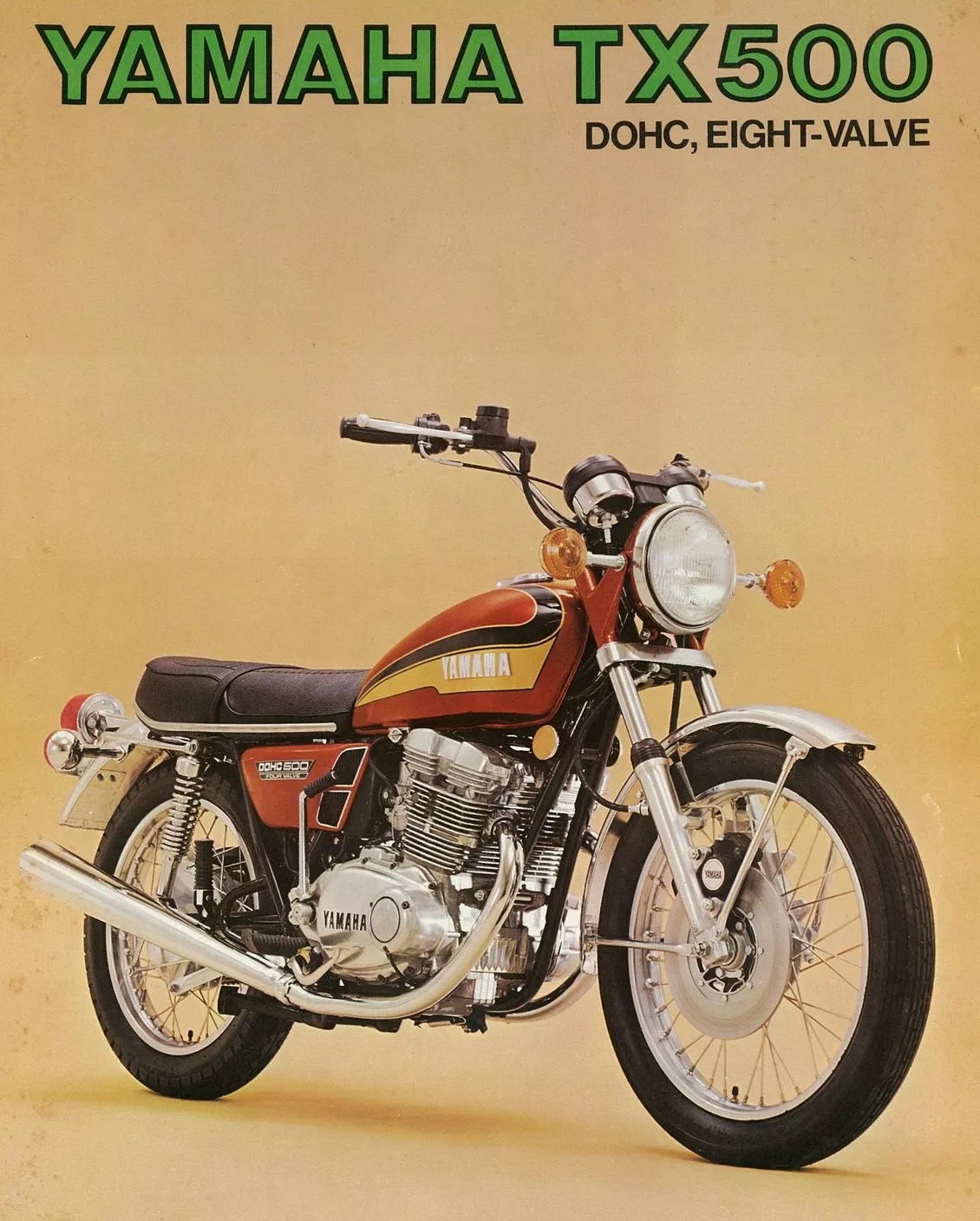

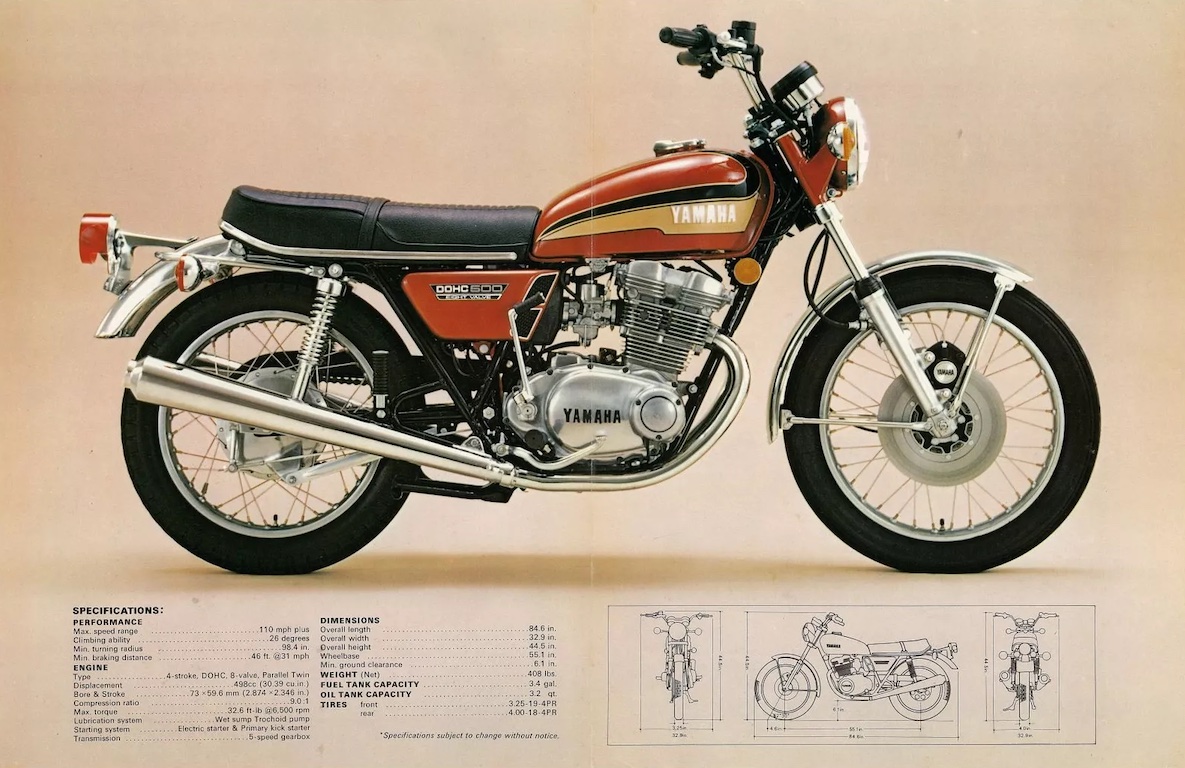

The mid-size option – TX500

Launched a little after the 750 was the TX500 (1973-74),

running a more sophisticated top end with double overhead

cams and four valves per cylinder. It too ran the

Omni-Phase balancing system, with more success.

However it too was troubled, with a reputation for

blowing head gaskets.

See the Motorcycle Specs TX500 data page

***

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact