Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

The fabulous

Vincent

Our bikes – 1952

Series C Rapide Touring

(December 2025, by

Guy 'Guido' Allen)

On the road – at

last! Getting to know our latest and most costly

acquisition has been a little convoluted and

entertaining

It’s been near enough to a year since I first handed

over what seemed like a giant wad of cash for a

motorcycle I had never clapped eyes on, namely the

1952 Vincent Rapide in touring trim. And it’s only in

the last week that it’s been registered on club plates

in sunny Victoria, Australia.

The most exciting part is I’ve now had my third ride

on the monster and am pretty happy with it. Even if it

fell on me…

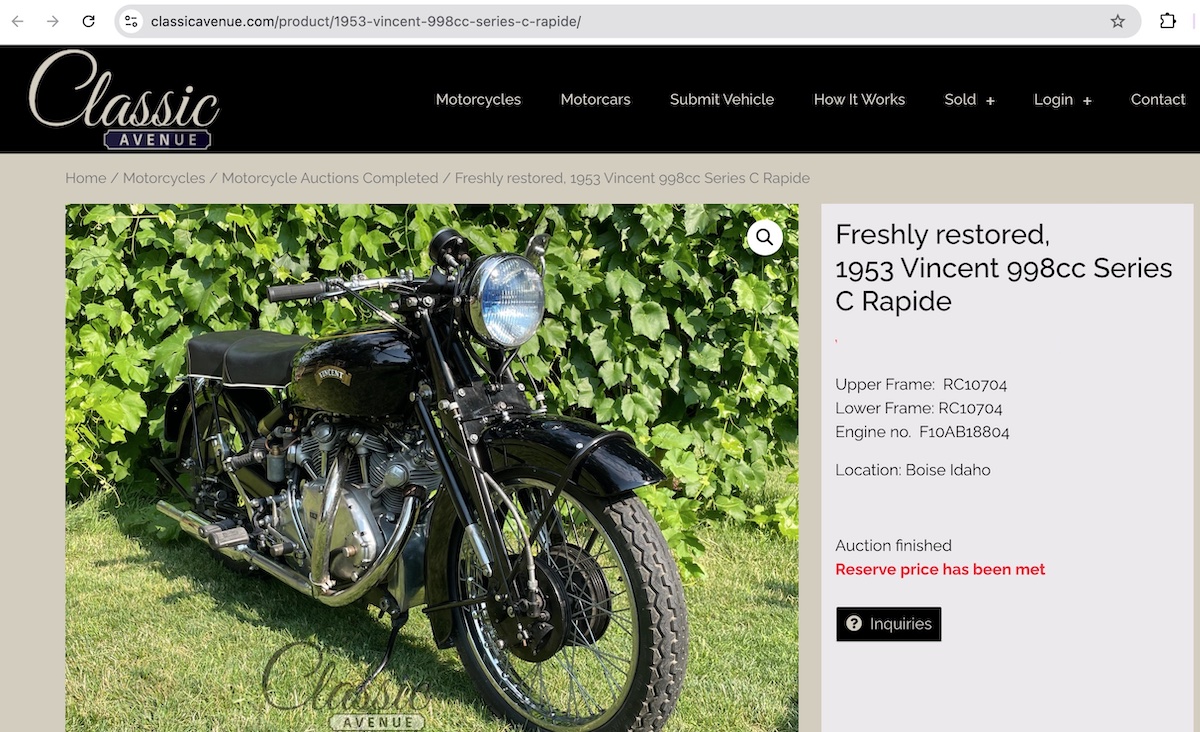

Looking back to late 2024, this thing appears on the Classic Avenue auction

website run out of the west coast of the USA by

a gent called Nick Smith. It’s advertised as a 1953

model, with a fresh restoration that included an

engine rebuild.

The bike was coming out of long-term ownership (since

1980) and failed to reach reserve. While I have never

met Nick, he is well regarded by locals I know and

trust – such as Jon Munn at

Classic Style and author Ian Falloon. Their

advice was Nick is a straight-shooter and good to deal

with. They were right.

So I asked the dangerous

question: how much would it take to buy the bike? The

number was Au$62,500 (US$42,000, GB£31,000, €35,700)

including auction fees. Then you need to add in import

tax and shipping costs – I was told by Falloon that

the best solution was hand over the whole importation

process to Jon Munn, who does it for a living. That

turned out to be great advice.

I briefly dithered over the purchase and Nick cheerfully reminded me that even an old man could start it, plus the pin-striping on the tank was done in gold leaf! Cheeky.

Landed, it owed me about

Au$68,000 (US$45,600, GB£34,000, €38,800). A lot of

money, but less than I’d pay for a machine of similar

quality on the local market. That all started just

prior to Christmas 2024 and we lost about four months

through holiday and shipping delays.

Along the way I got in touch with the HRD Vincent Owners Club in

the UK, looking for documentation on my example.

The initial and somewhat spooky response was, “we

thought that bike was in the USA”. It then asked for

photos of assorted numbers stamped into the main and

rear frame, and the engine. Once we got through that

little hurdle, the club was able to provide an

extraordinary suite of documents, including a delivery

docket from 1952 and confirmation the Vincent was in

fact ‘correct’ with all the right numbers ex-factory.

That underpins its value when, eventually, I may have

to pass it on.

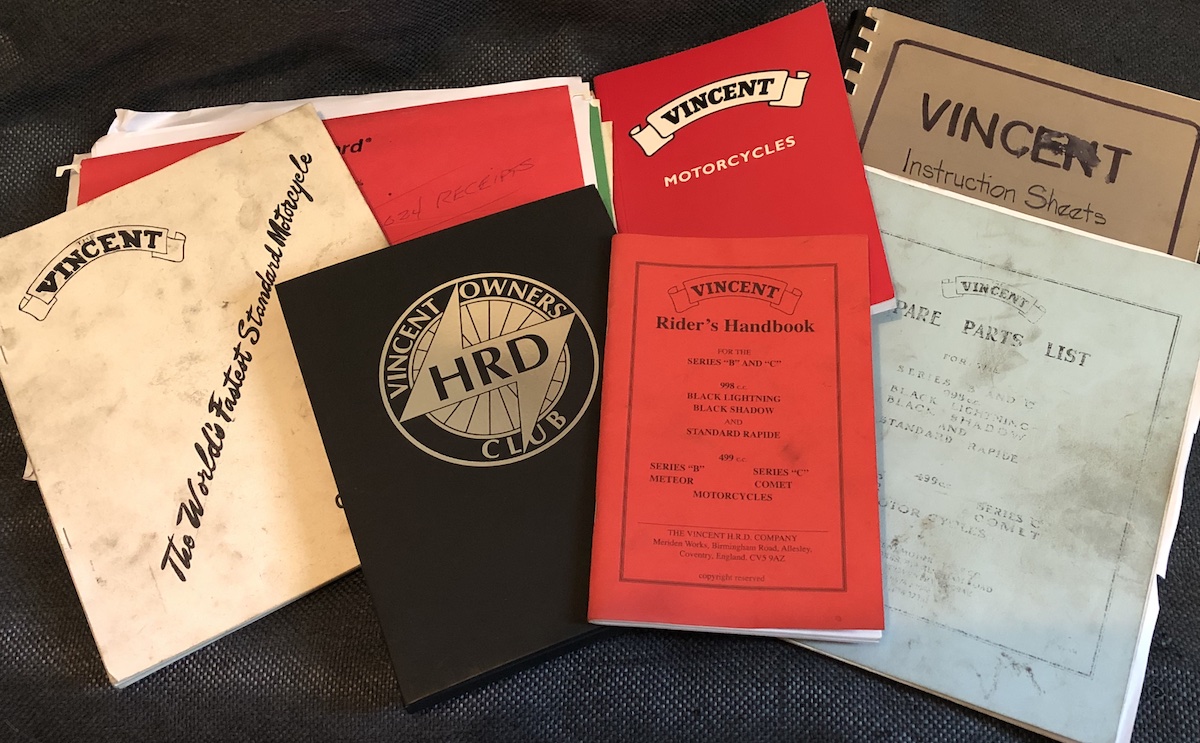

Since we’ve gone down that rabbit-hole, good paperwork is crucial for a motorcycle like this if or when you go to sell it. I’ve put together a physical brief case (yep, really) of paperwork going back 40-plus years, in addition to assorted manuals, parts cattle dogs…you get the gist. Plus there is a comprehensive digital folder.

You might notice I

referred to this variant as a touring. It runs the

same engine and chassis as a ‘sport’ Rapide. The

differences are a smaller front wheel (down from 21

inches to 19), deeper valanced guards in black steel

rather than aluminum and taller handlebars (mine has

the 'sport' flat bars). That’s about it. Of course

variations could be ordered from the factory.

When it landed, the motorcycle was fine – exactly what

Nick said it would be. I had a few little issues to

attend to such as converting the headlamp from the

right side of the road to left, oh and fitting new

tyres. The rubber was well-aged, with the front

pre-dating date stamps on the sidewall (!) and the

rear produced about the time ghetto-blasters became a

thing. Dunlop still makes TT100 replica rubber, which

was a perfect replacement.

In any case, I would

have fitted fresh rubber and changed the lubricants as

a matter of course. At least you then have a known

starting point when it comes to servicing. And the

costs are insignificant when compared to the value of

the machine.

Just down the road from me is one of the country’s most-experienced Vincent owners: Phil Pilgrim from Union Jack Motorcycles. Though his business is all about historic Triumphs, he owns the Vincent used for the famous (infamous?) Australian Chiko Roll advertising campaign poster, and has hosted several more. He fitted the tyres, with the proviso I gave him the wheels and not the whole bike.

Then I had to learn how

to remove the wheels, which can be done largely

without tools. That’s because the bike is festooned

with Tommy bars – essentially fasteners with giant

handles. Very practical. However you also need to get

your head around completely different architecture

when compared to now – such as dual drum brakes on

both the front and rear, all cable-operated. In the

case of the rear, one of them is nestled in behind the

chain drive. We are dealing with weird cattle.

When you need instructions (and most likely will)

there is plentiful documentation out there, including

factory owner manuals – 70-something years down the

road.

As for a headlamp

exchange, in the short term I’ve simply gone for a

modern lens unit with an LED bulb. The latter was

chosen for its modest draw on a 6-volt generator with

limited resources. I have other more age-appropriate

alternatives in the shed, and will investigate them

later.

Since we’re on the subject of lighting, this bike is running a Series D rear lamp, which is practical. I left it there for the roadworthy check and will soon exchange it for the period-correct Miller-style ‘Stop’ lamp.

As for starting the thing, it’s usually dead-easy. Because mine is a Series C, it has automatic advance/retard for the ignition and so all you do is flood the twin carburetors with the ticklers and set a little throttle. There is a valve-lifter lever that lets you take it over compression, and then you can swing at the kick-starter. Normally, this one gets going by the third kick. You get that big V-twin rumble which at 58 degrees is very different to anything else out there. Keep the throttle active for a few minutes and it settles into an idle.

The transmission is typical for the period, with a

one-up and three-down pattern on the right-hand side.

You also have a little neutral-finder lever (which you

use by hand) forward of the gearshift pivot point.

Getting away is standard

1940s to 1950s V-twin, which is you don’t need many

revs and don't worry too hard about finessing the

clutch. Point it in the right direction and cut it

loose, keep rolling into the throttle. That said, the

Vincent clutch is better than many for the period.

There is loads of torque and the entire thinking of

riding the bike is different to a modern equivalent.

I have been fortunate enough to ride a Series B Rapide

out in the country, with no strings attached, maybe 40

years ago. Why that happened is a story for another

day, and I never forgot the experience. I thoroughly

enjoyed it and then had no urgent desire to own one.

But maybe it planted a seed.

My latest ride got off

to a rough start. The valve-lifter had ceased working

and I suspect it’s because one of the washers for the

cable adjustment had jumped ship. That means you’re

trying to turn it over against compression, of which

this machine has plenty. Combine that with a smooth

concrete workshop floor and a side stand that is iffy

as a kick-start platform and the inevitable happens.

The side stand folds up unexpectedly and Muggins ends

up underneath the Vincent. The good news is the bike

hasn’t a scratch on it. I, however, was limping for

the next few days.

No matter. Go home, get the electric

roller starter (must do a review on that…) and

we got it running. Of course I was worried the damn

thing would stall on the way home, but it didn’t.

I’ve previously owned two 1947 motorcycles: a Sunbeam S7 and Indian Chief (above). They – among other weird purchases – introduced me to low expectations when it comes to braking and handling, and a high degree of rider involvement in the case of the Indian. We’re talking of a three-speed hand-change ‘crash’ gearbox (no synchro) with foot clutch and manual advance/retard for the ignition.

In the light of that

experience, the C-series Vincent is bloody wonderful.

Its transmission is smooth, if slow, and takes a fair

bit of authority to make it from first to second.

The brakes are decent spec for the era, with dual single leading-shoe drums at both ends. It takes a little care to set them up so they are more or less synchronised and, when they are, they work okay.

The handling is a little

weird by modern standards – it will punish indecision.

This series benefits from having an hydraulic damper

on the front end, aka the Girdraulic.

Out back you have a remarkably advanced

cantilever rear end with twin suspension units.

This is one of those

situations where you think ahead – have a corner line

in mind and get into the throttle, knowing you’ll just

have to accept any mid-turn crap. It does pretty well.

You might get the odd head-shake, but confidence is

everything in that situation.

To get speed out of the

thing, we’re talking about building momentum rather

than extreme acceleration. A Rapide runs with about 50

horsepower and is capable of 110mph (180km/h) – it

doesn’t sound like much now, but back then it was

quick. And, as Pilgrim has assured me, it is one of

the few motorcycles of the era which could perform at

a high level for days in a row and come back for more.

Now that we’re getting to know each other, it’s time

to take the relationship to the next stage – a pukka

ride out into the country. Wish us luck…

***

A little more weird cattle stuff...

There are two sidestands on the front – one each side – which can be configured to lift the front end off the ground.

Out back there is another stand to get the rear end off

the ground. Note the hinge in the rear guard to enable

wheel removal.

And we had to leave this badge in place, given it defines

where the motorcycle spent the previous 40 years.

Now that's a fuel tank emblem deserving of admiration...

***

Subscribe to our

free email news

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Top banner pic by the talented Stuart Grant!

Archives

Contact