Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Future collectible: Suzuki GSX-R1000

(by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen, Apr 2021)

Litre Land

Suzuki’s first GSX-R1000 was a watershed development and is now getting hard to find

The change to the new millennium – the 2000s – wasn’t simply an event of world historical importance, it also marked a changing of the guard when it came sports motorcycles.

Legends such as the Suzuki GSX-R series were well established by now, with competitors such as Honda’s Fireblade often raising the stakes.

Through 1999 to 2001 we saw a new generation of rocketships launched to tempt the motorcyclist’s palate. MV Agusta announced its comeback with what was arguably Massimo Tamburini’s second most-important design masterpiece (after the Ducati 916), the F4 750.

Over in the east, Yamaha launched its R1, which was a game-changer and smart collectors have been preserving good ones for some time now. Next? Well prominent among the offerings was Suzuki’s GSX-R1000, picking up where the R1 started and shifting the proverbial goal posts a long way.

Lighter and more powerful than the R1, it proved that Suzuki had – with litre-class motorcycles – rediscovered its mojo.

This quote from Motorcycle Online pretty much sums up the response, after its world launch in at Road Atlanta in Georgia (USA) in late 2000: “There is, of course, no rational reason for the GSX-R1000 - its purpose is all about adrenaline spikes, filling that need for speed, and finally making sportbike junkies the world over believe that fast enough really is fast enough. Based on the incredibly competent and compact GSX-R750, this newest open class contender has raised the bar for power output from a given displacement and then wrapped it up in a chassis that will make real racers smile.”

It’s worth stepping back just a minute to look at what came before it: the last of the GSX-R1100s, (above) which ceased production in 1998 for the 1999 model year. Initially (from 1986) the 1100 was a bigger 750, all slab sides, minimal niceties, light weight and lots of attitude (below). It was, literally, an endurance racer with lights.

Over the years it got bigger, heavier and more sophisticated, eventually switching from an air/oil-cooled powerplant to liquid-cooled. They were powerful and fast, but were more sports-oriented sports tourers than stripped-back true sports bikes. (The late models can still be great bang for the buck in the used market.)

See our GSX-R1100 buyer guide here.

There was this long uncomfortable silence for the best part of a year, while the GSX-R name continued primarily with the 750.

Then, with the launch of the K1 GSX-R1000, we got to learn that it was worth the wait. Like the original 1100s, the new chap (actually 988cc) was essentially a 750 on steroids. But the sophistication of the engineering employed by motorcycle designers had moved up several notches. We’re not talking just bigger pistons and a few extra gussets in the frame. No, not at all.

The folk in the secretive world of model development had been far more subtle. The frame was similar to the 750 but featured thicker walls where required – in fact the torsional rigidity was sufficient to give a grand prix bike something to think about.

And the engine. It was no wider than the 750, and just a touch longer and taller. That enabled the designers to keep the whole package down to very compact proportions. Inside, the pistons were actually lighter than the 750 items, though substantially bigger.

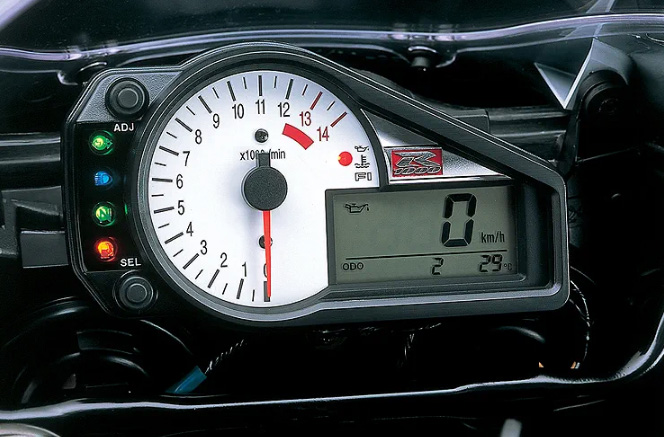

Electronics played a big role too, with a computer-controlled exhaust collector valve, similar in concept to Yamaha’s EXUP system, plus a secondary butterfly in the throttle that was also dictated to by the ECU. Of course, it was fuel-injected.

As for the raw stats, we were now edging close to the horsepower per kilo benchmark, that was to be comprehensively broken a few years (several updates and two generations) later with the K5. For the K1 (and the K2, which was mostly a graphics update) we’re talking 161hp and 170kg dry weight. Even today, that’s a formidable set of numbers.

As for the chassis, you’re dealing with fairly high-end Kayaba suspension hanging off the twin-spar alloy frame. The front featured nitride-coated (for lower stiction) 43mm upside-down units, with a full range of adjustment. Out back there was a monoshock with piggy-back reservoir and, again, all the toys in the adjustment department.

Tokico provided the brakes – six-spotters up front working 320mm discs, which were all the rage back then. If you didn’t have six-piston calipers, you weren’t one of the cool kids. Of course as time and development has marched on, we’ve discovered a good set of radial-mount four-spotters can be better.

The rear wheel settled for a far more pedestrian two-piston caliper working a 220mm disc, there more as an optional rudder than an actual device for stopping.

No, there was no ABS – though it existed on other machinery, it was still a long way from market acceptance on sport bikes.

Using the terms ‘comfort’ or ‘practicality’ may seem a bit out there, but the GSX-R wasn’t too bad in that direction. It was at least a workable road bike, with surprising civility if ridden with something approaching restraint.

Cut loose on a racetrack and it was, for its day, a formidable bit of gear. It represented a significant performance step and, for mere mortals, it took a while to get your head around the performance. A 750 on the same track could feel like a much more manageable package, even though the 1000 wasn’t much bigger or heavier. In fact, the 750 was only four kilos lighter and had the same wheelbase! However the big chap had far deeper reserves of torque, and 20 extra horses, which meant recalibrating your throttle hand when hustling out of tight turns.

In service, these things have no serious issues aside from normal wear and tear. The engineering was good from day one and, so long as they were maintained well (these are, after all, a high-performance bit of kit) they should be bulletproof. The other aspect is most will have spent very little of their lives working hard, as you just can’t wind them out anywhere outside a racetrack – at least not without risking life and licence.

They’re still a very fast, responsive and rewarding ride. One area that could do with an update is the brakes, however some fresh braided lines, fluid and probably some softer compound pads will take care of that. And a new set of premium tyres.

Freshen up the suspension – a rebuild will do – and you’ll have a very handy toy, despite its age. As with a lot of sports bikes, your challenge will be finding one that hasn’t been messed with beyond recognition (almost all of them have aftermarket mufflers, so that’s not a big deal), or simply treated with contempt as a throw-away.

Good ones are not easy to find, however high-milers start around $7000. Incredibly, we’ve seen people asking close to current new prices for very clean low miler (20-30,000km) K1 or K2s. Something with double those kays (50-60,000km) with evidence of regular servicing, would be high on my shopping list at the right price.

You can only weigh up the value on a case-by-case basis. Just keep in mind that, if you must have one, a good example requiring little or no work would usually be cheaper in the long run than something needing a complete overhaul. Although the ransom being asked for some early examples may challenge that calculation.

So where do they stand in the pantheon of Suzuki history? They’re unquestionably significant. First-model GSX-R750s and 1100s are important, then this is the next sports weapon on the list. Happy hunting…

Good

Fast

Well-sorted

Bad

Hard to find a good one at a reasonable price

Useful resources:

Suzuki GSX-R – a legacy of performance

Book by Marc Cook, produced by David Bull Publishing.

Suzukicycles.org

Online Suzuki index.

SPECS:

Suzuki GSX-R1000 K1 & K2

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline four

CAPACITY: 988cc

BORE & STROKE: 73 x 59mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 12:1

FUEL SYSTEM: Fuel injection 42mm throttle bodies

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Alloy twin-spar

FRONT SUSPENSION: Kayaba USD full adjustment

REAR SUSPENSION: Kayaba monoshock full adjustment

FRONT BRAKE: 320mm discs with six-piston Tokico six-piston calipers

REAR BRAKE: 220mm disc with twin-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY WEIGHT: 170kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 830mm

WHEELBASE: 1410mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 18lt

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: 17 x 3.5-inch 3-spoke cast alloy 120/70 ZR17

REAR: 17 x 6.0-inch 3-spoke cast alloy 190/50 ZR17

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 119kW @ 10,800rpm

TORQUE: 110Nm @ 8500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE WHEN NEW: Au$16,500-17,000 + ORC

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact