Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Future collectible – Kawasaki ZZ-R1100

King Zed

(September 2020)

by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen

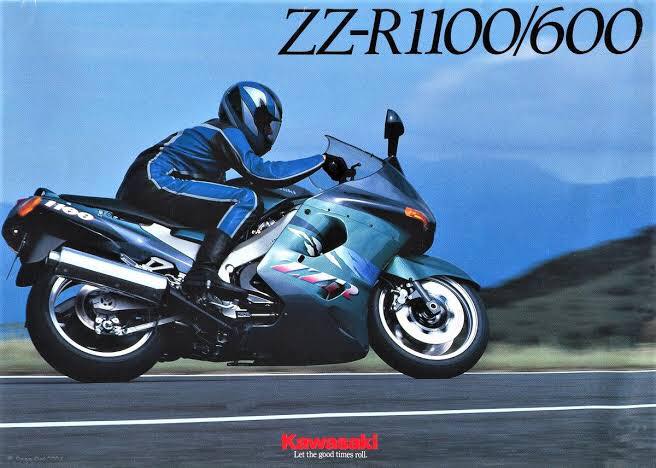

When sports-tourers ruled the earth, Kawasaki was king

It’s fair to say things were different back in 1990, certainly in the motorcycle world. Where cruisers and adventure tourers now tend to dominate the thinking of the market, back then it was sports tourers and sports bikes. They were the reputation-makers for your brand.

In Kawasaki’s case, the leader bikes had started back in 1984 with the GPz900R (above, see our GPz900R owner story here), its first liquid-cooled four which back then doubled as sports bike and sports tourer. Then came the GPz1000RX.

By 1988-89 the leader bikes had split into two branches: the ZXR750 sports, in response to the then new world superbike championship, and the ZX-10 sports-tourer (below) with its 270km/h top speed potential.

In 1990, there was unquestionably a buzz in the market about the new ZZ-R1100. It promised to be the fastest thing you could buy on two wheels (despite monsters like FZR1000s and GSX-R1100s getting around), while being a civilised ride.

As is typical of these motorcycle arms races, it didn’t take a huge jump to get the ‘world’s fastest’ gong: 285km/h did the trick. It took Honda another six years to wrest it off the Kawasaki, with the Blackbird at 290km/h.

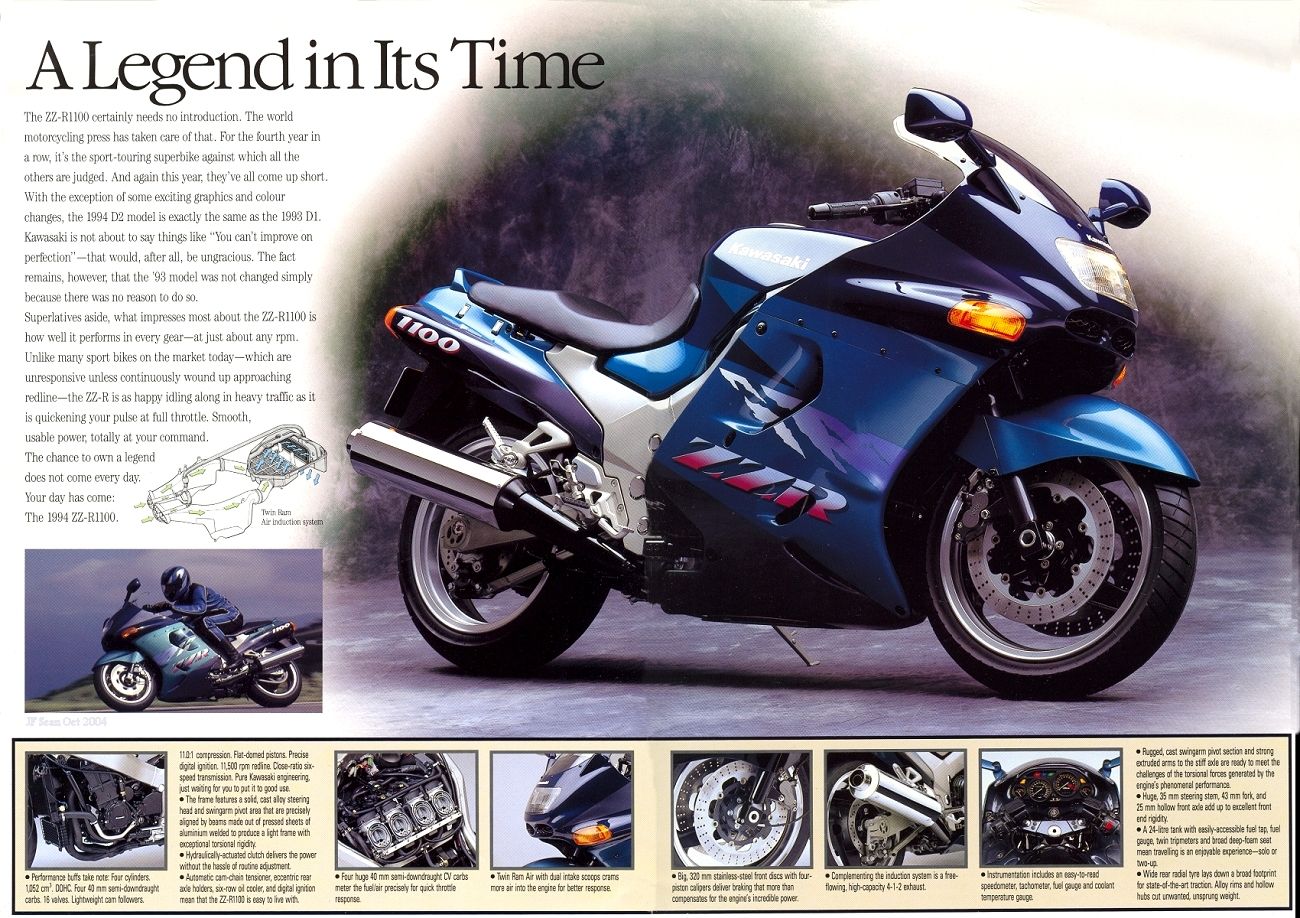

To achieve this, Kawasaki did a massive redevelopment of the ZX-10. Near enough to a clean sheet of paper, though there were obvious references. The twin-spar aluminium frame was beefed up considerably, while the front fork went from a 41mm to 43mm diameter.

Suspension at both ends was revised, as were the brakes, of course. Up front the discs went from 300mm with two-piston calipers to 320mm with four-spotters. That lot sat on new 17-inch radial tyres, which were still a bit of a novelty at that stage.

As for the engine, it bore an external resemblance to the ZX-10 unit, but next to nothing is interchangeable. Capacity went up to 1052cc, carburetion had been bumped significantly to a bank of 40mm units, while compression remained 11:1.

And the end result? A claimed 147hp (108kW) peak power at 10,500rpm, with 110Nm torque at 9500. That represented more power 500rpm higher up the range, and more torque 500 lower.

Now the weird thing was when you walked up to the new toy, it looked less slab-sided and more compact than its predecessor, but it was largely a visual trick. In fact, the ZZ-R1100 stacked on an extra 5mm in wheelbase and around three kilos. Despite that, it felt more nimble.

Typically for the class there was a fairly long stretch to the handlebars that suited medium to taller riders best. Seat height was down a touch, while the overall accommodation was typical sports-tourer – slightly lean-forward and good over long distances.

There were numerous practical touches on board, such as the dual trip meters, or the folding luggage strap hooks at the rear. Fuel range was decent, with 21 litres on board.

Like a string of liquid-cooled Zed motors, this one had a bit of a rumble going on at low revs, but by 3000-4000rpm settled into an uncannily smooth operation. Five kay-plus and the thing turned into a jet. Power delivery was entirely predictable, but there was something about it that invited the inner hooligan to pop its head up every now and then.

For its time, it was a very tidy handler. A little ponderous at really high speed, but that wasn’t such a bad thing – at least it was ultra stable. At anything resembling normal road velocities, it tipped in nicely and held its line well. The front end could ‘walk’ a little if you opened up the taps early on an exit, but overall it was a very civilised piece of machinery.

To my mind, as a ride it was the pick of the lineage, since the GPz900R.

The model lasted all the way to 2001, after which it was replaced by the much under-rated ZZ-R1200. During that time there were 12 models across two generations. The significant change-over point is the D-series, which started from the 1993 model year (which means it could have been built late-1992).

Numerous alterations went into the D, including several mechanical changes, a stronger rear subframe and floating discs up front. There were some styling changes, where the air intake in the fairing nose was changed from a single to twin ‘nostrils’, the fuel tank capacity increased to 24 litres and a larger volume exhaust fitted.

While the D made no additional performance claims, it did according to all reports pick up some useful midrange urge. However the original C-series was hardly a shrinking violet in that department.

ZZ-Rs proved to be remarkably trouble-free over their lifetime. On the first C-series, there was the occasional issue with second gear, generally if the bike was owned by an enthusiastic wheelie-hound.

On early Ds, there were a few reports of pitting on cams. The speculation was this tended to happen if the bike was left idling from cold for long periods on the sidestand, starving the high end of the cams of oil.

In either the case of the C or D, the issues were very much in the minority and anything that’s okay at this stage in its life would be a good bet. Really, what you’re buying into is a big strong motorcycle which, despite its age, has huge speed potential.

So what’s out there in the market? There are a fair number for sale, often with high mileages. These are the sort of motorcycle that really was used. Prices range from around $2500 to $8000.

For the would-be collector, the first C generation is the safer bet, though I wouldn’t be afraid to buy a D. In fact, I’d let condition rather than generation make that decision.

As with all big performance motorcycles, the consumables are a significant running cost, so things like tyres, chains and brake rebuilds can often be let go and can change a ‘bargain’ into a shock to the wallet.

Because of their age, early versions are just starting to get on the collector radar. Victoria with its 25-year rule is already allowing early bikes on to club permits. Other states with their 30-year rules aren’t far away and that will have an impact on the values of good examples.

Get the right bike, and you’ll be genuinely surprised at how good it is. Big, sure, and not quite as communicative as a lot of current kit, but still a very quick and capable ride. And, for its time, a true hero model.

******

ZZ-R1200

With Honda and then Suzuki claiming bragging rights in the mega sports-tourer class with the Blackbird and then Hayabusa, Kawasaki decided to counterpunch with the ZX-12R sport-focussed Ninja, thus relegating the ZZ-R name to slightly more gentle duties. The answer was the ZZ-R1200, which claimed a very healthy but no longer world-beating 160 horses (120kW). It represented a significant handling upgrade from the 1100 and was a worthy if less performance-focussed successor.

SPECS:

Kawasaki ZZ-R1100 C-series

Good

Very quick

Handles nicely

Lasts

Not so good

Too tall and long for some

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline four

CAPACITY: 1052cc

BORE & STROKE: 76 x 58mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 11:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 4 x Keihin CVK40

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Twin-spar aluminium

FRONT SUSPENSION: 43mm fork with preload and rebound adjustment, 120mm travel

REAR SUSPENSION: Fully-adjustable monoshock, 112mm travel

FRONT BRAKE: 320mm discs with 4-piston caliper

REAR BRAKE: 240mm disc with 1-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY/WET WEIGHT: 233/256kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 780mm

WHEELBASE: 1495mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 21lt

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: Cast alloy 120/70-17

REAR: Cast alloy 180/55-17

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 108kW @10,000rpm

TORQUE: 110Nm @ 9500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE WHEN NEW: $11,200 + ORC

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact