Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Indian

Summer

A

new range for the revived marque

Ed's note: this is the report

from the August 2013 Australian launch of the

new Polaris-designed Indian motorcycles

Words: Guy 'Guido' Allen; Pix: Lou Martin, Gold & Goose

It could only happen in Byron Bay. There, in

amongst the pack of shiny new Indian motorcycles

was a Bhuddist monk, grinning from ear to ear,

asking questions about the bikes and taking

photos. You couldn’t help but wonder that, if the

machines weren’t being so closely supervised,

whether he would be tempted to quietly slip away

on one.

It’s not every day you get to attend the relaunch of a brand and Indian’s has been what seems a like a long process. First there was the long and involved series of teaser sound tracks and images and TV ads, then the Sturgis launch with a simultaneous event in Sydney, then a Melbourne dealership launch and now, finally, the actual ride event. It was hosted in northern NSW not just for the local market, but also as a rolling series for most of Asia.

If you’ve been watching the international hoopla, you could be forgiven for missing the fact that parent company Polaris has pulled off a major feat in getting these machines to market so quickly. It only finalised the deal to buy the brand in April 2011 – so it took a little over two years to get from a blank sheet of paper to the finished product on the road. It’s a phenomenal effort.

WHAT’S THIS THING CALLED, LOVE?

Indian’s launch range consists of three models: the standard Chief, the Chief Vintage with soft removable panniers and quick-release screen, plus the top-of-the-line Chieftain, with fixed fairing, electrically-adjusted windshield and hard panniers. They all share the 111 cubic inch (1811cc) air-cooled two-valve engine, with fuel injection, mated to a six-speed transmission via a wet clutch. Final drive is by belt.

The level of electronic equipment

on the stock bikes is high. Everything gets

keyless starting, fly-by-wire throttle,

spotlights, cruise control and ABS. The Chieftain

adds stereo, Bluetooth and tyre pressure

monitoring.

The big surprise is in the

chassis. All three machines score a multi-piece

alloy frame (Polaris prefers the material for its

ability to allow a dead-accurate and consistent

result), with the Chief and Vintage sharing

specification and the Chieftain running – believe

it or not – more nimble geometry. It has a steeper

head angle (25 degrees versus 29), forks set

slightly back rather than forward of the steering

head, and a shorter wheelbase (1669mm versus

1730).

Why? The reasons are mixed. For a start, the Chieftain (above) wears the geometry the engineers would prefer on all the machines – they say it gives good high-speed stability while keeping the bike relatively easy to manoeuvre. But, according to project leader Gary Gray, that geometry simply didn’t look right on the naked Chief and semi-naked Chief Vintage. The fairing on the Chieftain disguises the lines better.

The suspension itself is a conventional 46mm front fork (with 119mm travel) and a rear single shock with preload adjustment. The Chieftain rear offers a little extra travel over the other two machines (114mm versus 94mm).

Braking is by four-spotters on

twin floating discs up front, with a single

floating rotor and a dual-spot caliper on the

blunt end.

ALL ABOARD

Having ridden a number of Victory

models (also from Polaris) over the years, I went

into this comfortable with the idea that the

company knows what it’s doing when it comes to

building a big V-twin cruiser. Frankly, it would

have been close to unimaginable that they might

have cocked it up – and they haven’t.

We had a roughly 200km loop over which to swap

bikes on the first day, then some free time the

next morning to do what we pleased. Enough to get

a reasonable handle on what they’re like.

Without doubt the engine is the

centrepiece and it’s hard to fault. Indian is coy

about the power output, but claims 119ft-lb

(161Nm, 16.5kg-m) of torque at 3000rpm. The

Chieftain tacho’s red zone starts at 5000rpm,

while 100km/h equates to 2300.

Throttle response is crisp. We got a decent range

of riding conditions and the engines performed

well. They’re lively, with the sort of fat

midrange you’d hope for on machines like this.

Performance pipes are available (with a flash tune to go with them), that offer a little extra lift without outrageous noise. Stand back, though, as you can expect a mad rush of aftermarket tuners getting on the Indian bandwagon. Out of the box, they’re already fast and I would feel any urgency to head down the hot-up trail.

The gearbox was another surprise – better than what’s being offered by Victory at the moment, with a lighter and more precise action. It’s very good and combines well with a light and progressive clutch.

Decent straight-line performance is backed up by a good chassis. Though we weren’t setting lap records, there were a couple of occasions when the bike I was on hit an awkward mid-corner bump hard and fast enough to generate a weave in most cruisers and it simply wasn’t happening.

Suspension rates seem well chosen,

while the cornering clearance is respectable, if

not limitless. The Chieftain has some real

advantages here, being noticeably more neutral and

nimble in its manner, with a little extra

clearance. Braking is strong, with decent feel.

None of these bikes are light – we’re talking of dry weights ranging from 350 to 370 kilos. However, for anyone used to handling big bikes, they don’t feel clumsy or difficult. The dynamics are way ahead of the vast majority of the cruiser pack. Really, you could put in some very respectable point-to-point times on any of these machines, particularly the bagger.

What’s not to like? The most

consistent grizzle to surface was the Chieftain’s

central dash screen was at times difficult to

read. Much depended on where the sun was in

relation to the bike, but a less reflective glass

with a higher contrast display would be welcome.

You still get a crystal clear view of the speedo

and tacho, so we’re not talking about critical

functions.

Fit and finish can be altered with

a host of accessories, including alternate height

screens. Of course you can dress to look the part

from a big catalogue of rider gear.

We don’t yet have fuel consumption figures, though

history suggests bikes like these should be able

to achieve mid teens or maybe even better per

litre. Combine that with the 20.8 litre fuel tanks

and you should have a decent range.

Finish on our examples was very

good, with plenty of nice touches, such as the use

of good quality leather for the seating.

Maintenance should be relatively light, given the use of hydraulic valve lash adjustment.

Would I buy one? Well, there are

two Indians in the shed already, and there is the

small matter of finding the money, but I certainly

wouldn’t rule it out. Pricing is competitive,

particularly when you account for the solid list

of standard equipment.

The fact they look good and perform well, along

with the historic name, should make them a

compelling option.

***

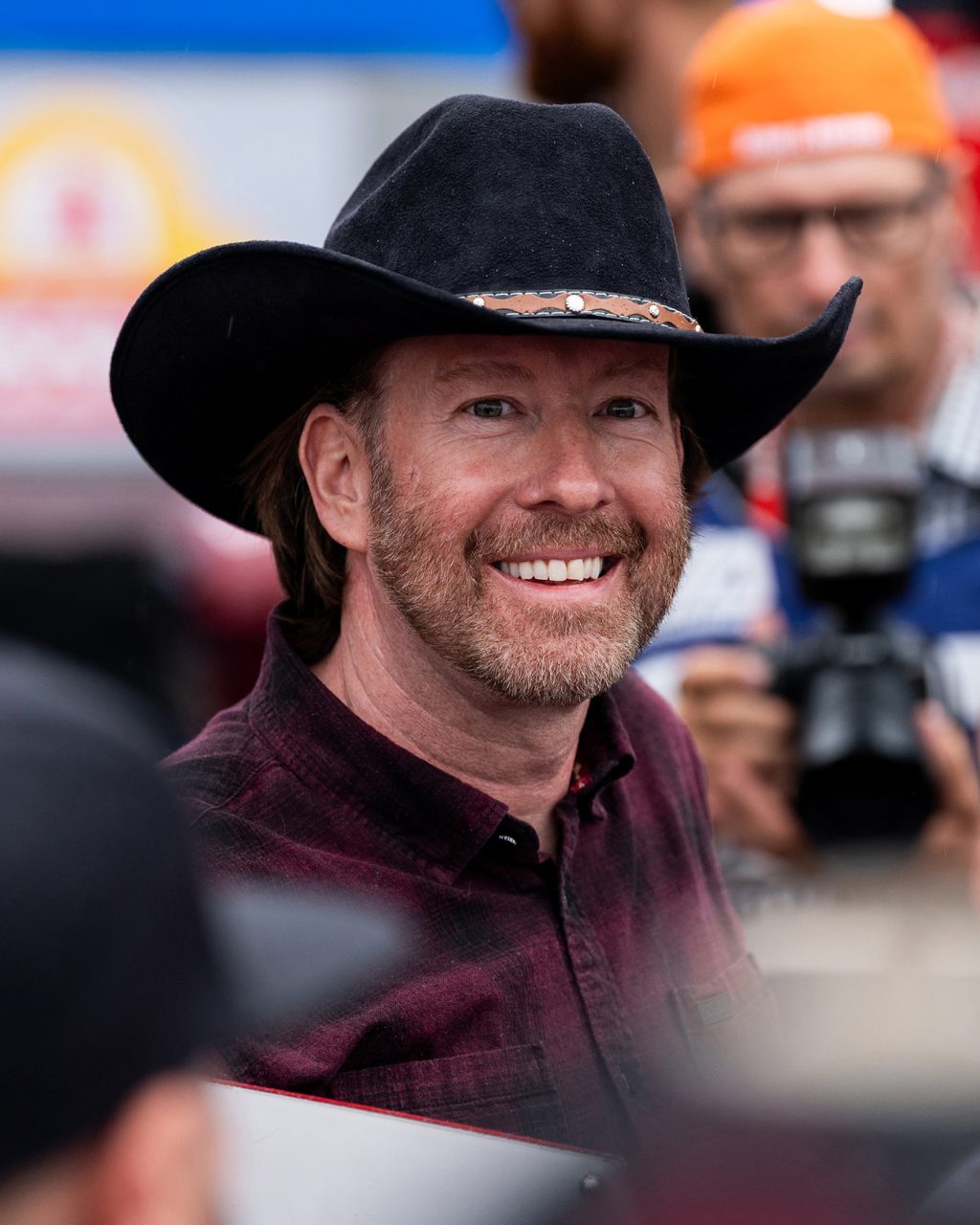

MEET THE CREATOR

Product director Gary Gray (pictured here in

2025) is a quietly spoken and surprisingly young

gentleman who clearly feels a strong passion for

his ‘baby’ and motorcycles in general.

“I live breathe, eat motorcycles,

and have been riding since I was 11 years old.” He

recalls hijacking a cousin’s bike and climbing

aboard using the front steps of the house, because

it was way too big for him.

Getting hold of Indian was,

however, a much bigger challenge. “When you get

handed the keys to this brand it’s an honour – an

honour to come to work every morning. Sometimes

you pinch yourself and say, ‘wow, is this really

happening?’

“I had one goal in mind for this line of bike: to

make the premium American motorcycle – I want

people to look at it and say that’s the best that

America can make.

“Indian’s had a troubled past – it’s been knocked down - but it’s still this brand that people wanted to come back.

“To keep people focussed, we developed a three-part strategy for designing the bike.”

The first (and most important in his view) was to honour their past. “When this bike came out, I didn’t want people to see it and say ‘what is that?’ I wanted them to see it and say, ‘that is an Indian motorcycle. These guys get it’.”

The second aspect was “just make it premium. There’s nothing lacking in terms of performance, or in terms of technology. In terms of chrome, there’s no bike that has as much as we have.

“The last element I think we had to bring is confidence.” He points out Polaris is forecast to be a US$3.8 billion company this year. “We’re a powersports company,” explains Gray, “We have all the operations, we have the infrastructure and plants now around the world. We go up against big brands, such as Honda, every single day.” He goes on to point out the company sells more off-road recreational vehicles, into the North American market, than anyone else.

“We know what we’re doing, we have

the funding and the backing. The other thing we

bring is a solid basis for a warranty that people

can count on when they buy.”

On developing the bike itself: “We’ve got a huge

brand history and that’s what we started with,

really trying to understand the brand.

“Then a group of us went – I think it was May 2011 – on what we called the Indian Heritage Ride. We took off on motorcycles…and what we were doing was visiting dealerships, visited our factory, visited a guy in western Iowa that had about 25 Indians.” The latter would delve into the shed, start one up – for example an early four – and offer them a ride. Gray talks of the fun and dramas of getting used to left-hand throttles, hand shifters and the like. It was “just really learning what an Indian motorcycle was – it was really important to us.

“A ton of research went into the project before we designed a bike.”

The process began with a mini conference, debating what some of the basics should be. Should they, for example, do a four? What about singles? The decision came down to a mix of customer expectations and what was financially realistic. A four hasn’t been completely ruled out – maybe one day.

“We start off with hundreds of sketches, whittled down to five finalists – from ‘mild to wild’. Take it to focus groups, then you pick one and take it to 3D. You have to see it in three D, so you can get a real feel for what’s going on with that design…it’s a long and involved process.”

For the design team, the model that presented an enormous challenge was the Chieftain, as Indian had never before built a ‘bagger’ – that is, a bike with fixed fairing and hard panniers. “What we did is look back to the designs of the time, the cars, the trains, the ships. We got inspiration from the streamliner trains, there were big, impressive and aerodynamic. To me those three elements are what a bagger rider wants.”

Gray went on to highlight the ownership people feel when they work on the machine. “People don’t (just) show up…everyone who works on the bike is personally invested in it.”

He says this is reflected in the level of attention that has been given to every detail – even the oil dipstick. “The original dipstick that was designed for the bike looked like crap,” he says, “The words I used were, ‘that wouldn’t look good in my lawnmower. This is an Indian motorcycle, this is going to be the premium motorcycle in America, we’re not going to put a dipstick in the bike that doesn’t belong in a lawnmower.’

“So we went back and redesigned this beautiful knurled piece. You can loosen it with your hand, but if you happen to over-tighten it, there is a tool to loosen it.”

Inside the small warbonnet-shaped tool are the initials of the people who have worked on the machine, and Gray goes on to say that there are a number of little engineering ‘easter eggs’ like that hidden around the machine.

When you throw a leg over one of

these Indians, you at least know it was designed

by someone who cares…

Ed's note: Gray was inducted

into the Sturgis Hall of Fame in 2025.

See the

story at Indian.

***

Specs: 2013-14 Indian Chief range

Likes

Fast

Handle well

Nice finish

Dislikes

Not cheap

ENGINE

Type: air-cooled V-twin with pushrod-operated two

valves per cylinder

Bore and Stroke: 101 x 113mm

Displacement: 1811cc

Compression ratio: 9.5:1

Fuel system: Electronic injection

TRANSMISSION

Type: 6-speed constant mesh

Final drive: Belt

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR

Frame type: Composite alloy

Front suspension: Conventional 46mm fork, no

adjustment

Rear suspension: Monoshock, preload adjustment

Front brakes: 4-piston 300mm twin discs with ABS

Rear brake: 2-piston, 300mm disc with ABS

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES

Dry weight: 353/363/370kg

Seat height: 660mm

Fuel capacity: 20.8lt

PERFORMANCE

Max power: Not stated

Max torque: 16.5kg-0m @ 3000rpm

OTHER STUFF

Price: $28,995/31,495/35,955 on road

Test bike supplied by: Indian Australia

Warranty: 24 months/unlimited km

***

See our 2015

Chieftain review

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact