Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Our Bikes - Honda CB750-Four K1 1971

(July 2020)

Stepping back in time

by Guy 'Guido' Allen; pics by Ben Galli Photography

It took several decades to once again throw a leg over a Honda CB750-Four - was it worth the wait?

There was a time, some four decades ago, when a very second-hand CB750-Four was my first 'big' bike. How times have changed. For a start, our definition of the term big bike has shifted enormously.

The history of the single-cam CB750-Four is all too well

recorded. It’s widely blamed for the death of the British

motorcycle industry in the late 1960s to 1970s, though

many now accept the commercial collapse was largely a

self-inflicted wound.

In any case, the humble CeeBee has developed legend status over the decades. It proved you could make a powerful and reliable multi while it rapidly changed our expectations.

I started riding five years after this bike was built and,

even then, the whole idea of an electric-start four was a

topic for debate. “It’s a car with two wheels missing,

mate,” was a very familiar argument. Too many cylinders

and too convenient seemed to be the thrust. The

implication was it wasn’t a ‘proper’ motorbike. A cynic in

those days might have suggested that, ipso facto, a less

reliable twin was a proper motorcycle. But who would be so

cruel? (And before you get upset, I also own a Meriden

Triumph...)

Former Motorcycle Trader mag Editor Greg Leech

is to blame for this addition to the shed at Chateau

Guido. He was the one who talked Brian Browne, ringmaster

at TT Motorcycles in Mornington (Vic),

into building a CB-based café racer as a give-away bike

for the mag some years ago. It was a stunner. Without that

connection, none of this would have happened.

I kept in touch with young Mr Browne and one day made the

mistake of asking what was happening with the gold Honda

in the corner. Given I can’t write an Irish accent, you’ll

have to do your best with this: “Oh that,” he said, “Well

I built that for myself but don’t get much time for it, so

I’m wondering why.” Okay…how much?

The number was up there for the time, but given it was a

top-to-toe restoration, done by a former Honda dealer who

could build in details no-one else could, it seemed

reasonable. Looking back, it was a bargain.

Its only wrinkle was Brian fitted a later fuel tank,

because he preferred a left-side fuel tap, when the

original was on the right. I’ve since bought an unrestored

early tank and put it away, which will be sold with the

bike. One day, far away.

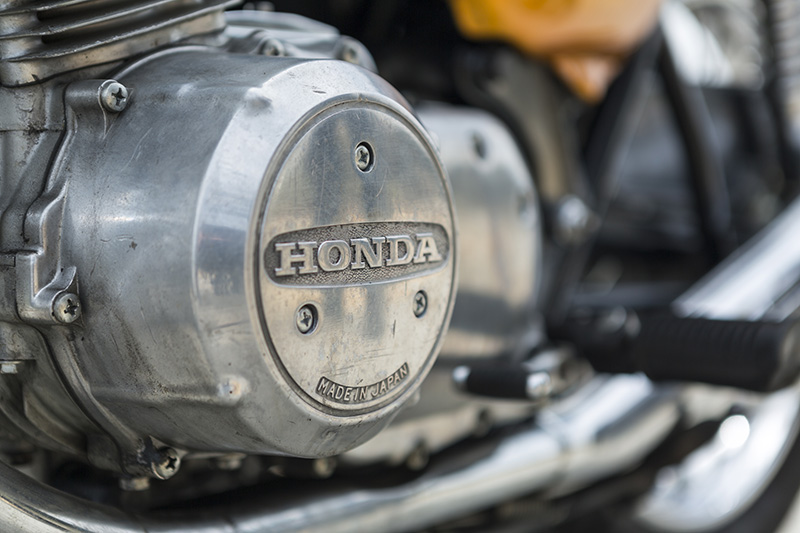

Honda’s first CB was the K0 launched in 1969, which have

become a hugely popular target for the investment end of

the motorcycle market. Those bikes now have dedicated

clubs and restorers. You can buy a fully

restored/remanufactured version, but don’t expect any

change out of US$40k (Au$60k) for a very early 'sandcast'

example. All up, there were 7414 units built with

gravity-cast engine cases.

Thousands of K0s and K1s were built, but survival rates

are incredibly low. Keep in mind there was a time when a

well-used one was worth next to nothing - it was just an

old Japanese bike. One of the reasons they found their way

on a trailer to the tip, which few people talk about, is

the engine’s Achilles heel was pin-holes for oil galleries

feeding the cam bearings and rockers. They were easily

blocked and scads would have died thanks to poor

maintenance and over-generous use of silicone-based gasket

sealants during rebuilds.

Thankfully, this one survived.

It had been over a couple of decades since I’d ridden one

of these things – I’ve owned three over the years – so I

was more than a little curious to finally throw a leg over

one.

Reaching for the ignition switch under the left front

corner of the tank was a little weird, though the

minimalist choke lever brought memories flooding back. So

too did the distinctive flat drone of the long-stroke

engine as it happily burst into life. I swear it’s unique

– there are lots of inline fours out there, but a CeeBee

has a cadence that is its own. For just a moment there, I

was 20 again.

Geez it’s heavy. With the wide bars, the lairy paint

scheme, and oddly menacing note from the engine room, you

would have felt as though you were dealing with alien

technology back in 1971.

Get it rolling and it’s a big happy motorcycle with plenty

of straight-line urge. The carburetion is good, it’s

smooth, and it’s a comfortable ride.

Tip it into a corner and you soon discover its

limitations. This resto includes the original FVQ rear

shocks – unkindly but accurately known in some circles as

Fade Very Quickly – and they’re ordinary. Comfortable in a

straight line, they bounce around menacingly when you are

pushing on and hit a series of mid-corner bumps.

As for the front brake, well, we're talking early

seventies – hardly a high point in disc technology. Treat

it with caution in the wet, as the polished disc takes

time to dry out and bite. It's okay in the dry. The rear

is a drum and works fine.

Past experience has taught me the frame is also severely

tested with any serious corner velocity – it can and will

flex. My 1975 T160 Triumph will run rings around it in the

handing stakes. Back off the pace to halfway sensible

cruising speeds and the situation is a perfectly happy

one.

With all those foibles, a well-built and cared for example

is ultra reliable – always the ace card in the Honda CB

playbook. It feels like it would take you across the

country tomorrow. Plus it's a smooth and throughly

enjoyable ride that you could happily plan to take away on

a long trip.

Of the classics in the shed, it’s the one that causes me

the least grief and is by far the most lairy. Now, where

are the flares and the gold chains? We need to dress up if

we’re taking it out for a ride…

***

Care & feeding

Oil is checked via a tank with a dipstick on the right side – this is a dry-sump engine – and regular changes are important. Both the bottom and top end bearings are plain rather than rollers, making good lubrication essential.

A note of caution when checking the oil: if it's cold and has sat for a while, expect a very low (but still visible) level in the tank. They have a tendency to 'wet sump' a little but, unlike (for example) a Commando of the same period, this isn't a problem. The real level will rise and reveal itself when the bike has run for a few minutes and warmed up. Use the latter to judge whether it needs more.

A CB of this age will be running twin sets of ignition

points, so you will need to get familiar with the

old-school idea of timing (static or dynamic) and

measuring point gaps. It’s not particularly difficult and

the skills transfer to many bikes and cars of the era. A

workshop manual is very useful.

Access for tappet adjustment is very good and the process

very simple. Similarly, access for the spark plugs is also

good.

If you're considering a top-end rebuild, be aware that lifting the head is an engine-out job. Not complex, but a bit of a bastard to do. The powerplant is a super-tight squeeze (there's a technique to getting it in and out of the frame) and you're strongly advised to have an extra set of hands to help out.

Parts supply is excellent. Probably the best source in Australia is Pud's Four Parts.

See the 1970 K0 road test from Classic Two Wheels

Identification

Here's a really good ID and restoration resource: honda750expert.com

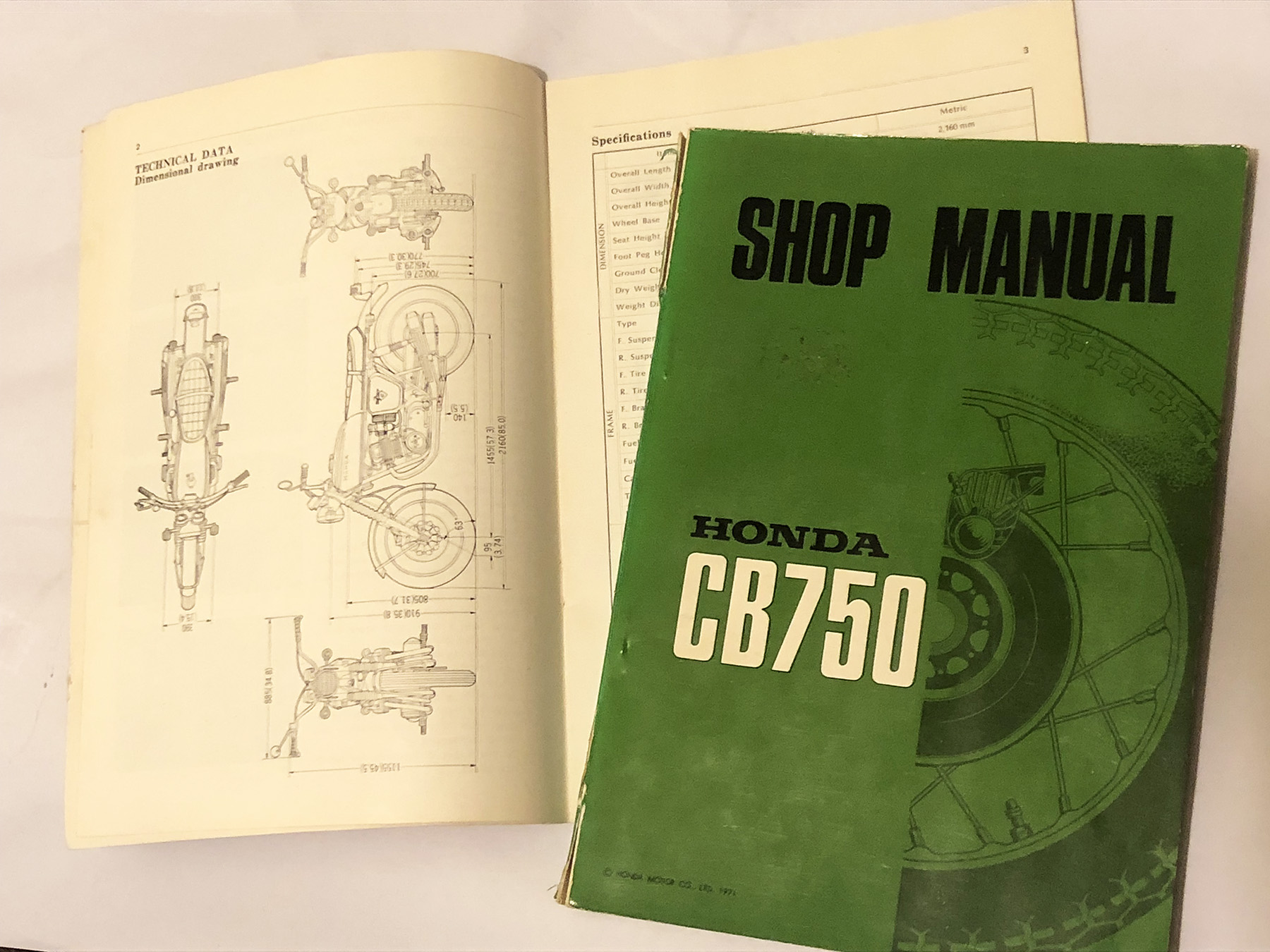

Workshop manual – a little story

Thanks to young Ian, an AllMoto reader, we managed to get our hands on these – 1971 Honda workshop manual and supplement for the mighty CB750-Four K1.

The books came with a bit of a story:

"Dad was a wharfie and one day he saw a red Honda four (a first model) come off a ship in a cargo net, which piqued his interest.

"So he took charge of it and waited for the owner to show up, which he did, shortly after.

"Turns out he was a Japanese guy and the first mate on the ship. He’d bought the bike in Japan and it went everywhere with him so that he could ride around the waterfront dock areas until the ship left. I’m guessing that if he was picked up for riding a strangely number plated bike he would soon be long gone and didn’t worry about it. Simpler days...

"Dad was riding an orange Suzuki Hustler at the time and they had a few short rides around Sydney together, checking out the sights.

"Anyway, they bonded, as only bikers seem to be able to do and Dad asked him if he could pick one up for him in Japan, to which the guy agreed.

"So, Dad handed over $900 and waited.

"Some months later, the ship returned and off came the red Honda again, followed by two crates.

"Inside the first one was Dad’s brand new gold K1 Honda. Inside the second smaller crate was a replacement exhaust system and eight tyres – four front and four rear! And the manuals, all for $900!"

---

SPECS:

Honda CB750-Four K1

ENGINE:

TYPE: Air-cooled, two-valves-per-cylinder, OHC inline four

CAPACITY: 736cc

BORE & STROKE: 61 x 63mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 9:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 4 x 28mm Keihin carburettors

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Five-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: twin loop steel

FRONT SUSPENSION: non-adjustable forks

REAR SUSPENSION: FVQ twin shocks, preload adjustment

FRONT BRAKE: single 290mm disc with single-piston caliper

REAR BRAKE: 178mm drum

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY WEIGHT: 226kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 800mm

WHEELBASE: 1453mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 18.2L

WHEELS & TYRES:

FRONT: 19-inch wire spoke, 3.25-19

REAR: 18-inch wire spoke, 4.00-18

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 50kW (67hp) @8000rpm

TORQUE: NA

TOP SPEED: 200km/h

STANDING QUARTER: 13.5sec, 160km/h

Before the resto

Here are a few pics of Brian's starting point for the resto...

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact