Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Future collectible – Triumph T300 series

(by Guy ‘Guido’ Allen, pics by Stuart Grant Photography, Ben Galli Photography & Triumph, Oct 2020)

Hinckley Heroes

The bikes that brought Triumph back to life

It’s difficult to imagine now, but when in 1990 Triumph announced it was re-entering the market with a new range of motorcycles, to be shown at the Cologne Show towards the end of that year, a lot of people muttered ‘not again’. I was one of them.

Triumph’s name – though much loved and with a huge history – was deeply tarnished at the time. People remembered the reliability issues, which became worst in the old Meriden factory’s dying days. First, parent company NVT (Norton Villiers Triumph) went belly-up in 1977.

Then, in 1983, the co-operative (which seemed to involve remarkably little actual co-operation) that battled on with the brand fell over as well.

Businessman John Bloor bought the rights to the Triumph name and leased it to Les Harris of Racing Spares, who built a small run of twin-cylinder Bonnevilles (above), closely based on the old Meriden design. Meanwhile Bloor hatched a plan to get serious about the brand’s resurrection.

So, 13 years after the rot set in, there was reason for cynicism when the all-too-familiar ‘Triumph rises again’ headlines began to appear. Ironically, despite my initial misgivings, I ended up working for the brand and owning several of its bikes.

Home on the range

Known as the T300 series, the range launched in the first few model years (1991-on) included four engines: 750cc and 900 triples, plus 1000 and 1200 fours. They were used across several revived old model names: Trident, Tiger, Thunderbird, Trophy and Daytona. Plus there were three new names: Sprint, the Speed Triple (a play on the old Speed Twin nameplate) and Super III.

Those four engines were essentially the same architecture, in three or four-cylinder form with short or long strokes. A short-stroke engine gave you a near enough to 250cc per cylinder (so a 750 or 1000), while the long stroke was closer to 300 (for a 900 or 1200). Add in what was more or less the same frame across the range and you have an exercise in creating the maximum number of models with the minimum parts inventory.

Triumph referred to this approach as modular, where you could effectively mix and match major components to come up with a new toy. It wasn’t an entirely new idea, but at the time Hinckley could claim to be the world’s most convincing exponent.

However Bloor could never have been accused of cutting corners in his efforts to revive the brand when it came to the engineering and construction. He ended up sinking hundreds of millions of dollars into the exercise, going to extraordinary efforts to bring much of the manufacturing in-house as soon as possible. The equipment was new, as was the purpose-built factory put up on a 10-acre (four hectare) site in sunny Hinckley – not all that far from Meriden and still very much in the Midlands.

In the saddle

The first example of the product I rode was snatched from Phil Pilgrim at Union Jack Motorcycles, who in turn had borrowed it from the then new importer, Peter Stevens. It was a Daytona 1000, and so had the short-stroke version of the four-cylinder engine.

Having got aboard with low expectations – at that stage I knew little or nothing of how much Bloor had thrown at the exercise – it turned out to be a bit of a shock. The thing was good. Really good. A touch top-heavy, but decent performance, sharp brakes, respectable suspension and well-finished. Wow.

If you got down to brass tacks, it wasn’t quite up there with the FireBlades or ZZ-R1100s of this world. You got the sense the development was maybe a couple of years behind. That said, it was a very acceptable piece of kit and it had that historic Triumph name emblazoned on the side. That last factor alone could claim a price premium for what was initially going to be a low-volume product.

In the end, the short-stroke engines disappeared, which sounded the death knell for the Trident 750 and the Daytona 750/1000 series – both are now quite rare. The reason? Everyone much preferred the longer-stroke engines, with the 900 triple proving to be particularly popular.

The base-model from 1993 was the Trident (above), a naked 900 with the 98hp (73kW) version of the engine (the same tune as the Daytona 900) and priced at $13,400 plus ORC. That compared to a FireBlade at just $1000 more.

I owned one for a while and what it never really got credit for in published tests of the day was being a genuinely quick and capable all-rounder. Like the whole range, it felt a little top-heavy – particularly when the 25 litre fuel tank was full. However if you were of medium height to tall, that wasn’t such a big issue.

There were some contrasts in the finish. While the fuel tank featured beautiful pinstriping done by hand, the instrument cluster looked underdone and was a bit of a disappointment, particularly compared to the sexier Speed Triple.

Speaking of which, the café racer Speed Triple (above) shared the Trident’s engine, but initially launched with a five rather than six-speed transmission. It was easily the sexiest-looking of the range and Triumph to this day has struggled to match its handsome lines.

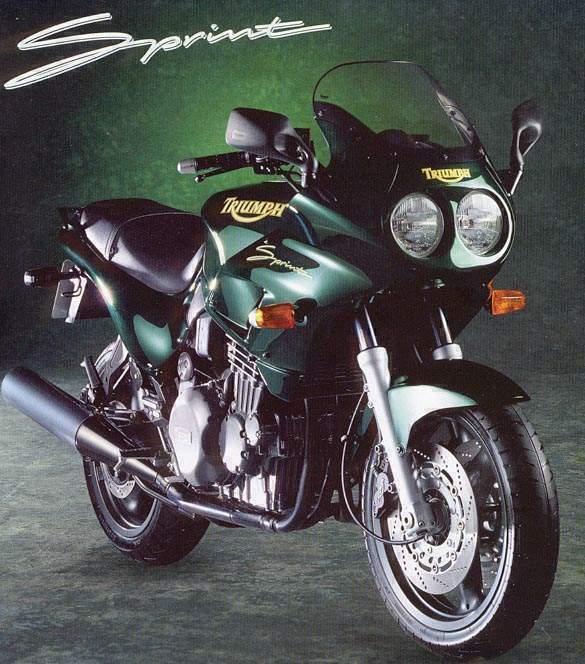

Rounding out the full-horsepower 900 range were the Sprint – effectively a Trident with a frame-mounted top fairing and upgraded front brakes – plus the fully-faired Trophy tourer and sports Daytona. There were two main variants: one with the ‘square’ tail section like the Trident and a later version (above) with a more rounded look.

Tiger hunt

But wait, there’s more! You also got a Tiger 900 adventure tourer, with the triple tuned for around 80 horses (60kW). In some situations, this was actually the nicest engine in the range – enough power to do the job and an easy-going loafing nature.

It’s become the most difficult of the range to find in good condition. Not a lot were sold, and it seems the few good ones left are being hoarded.

Finally, there was the Thunderbird (which ran some significant mods to the engine cases by the 1995 launch), rated at around 70hp (52kW). It was one of those bikes that was incredibly quick and capable if you assessed it as a cruiser (which was Triumph’s intention) but didn’t score so well as a 900 naked, which all too often is what happened. Topping off the presentation was a revival ‘portcullis’ tank badge that talked to the marque’s history.

There was a later version called the Thunderbird Sport, which gave the model a more aggressive look and was the pick of the series as a ride.

Then we get to the big boys, the 1200 fours. There were only two: the 114hp (85kW) Trophy tourer (above, which along with the 900 version underwent a major restyle in 1996), plus the 147hp (110kW) Daytona. The latter was getting up there in price: $17,500, plus ORC, at launch and bumped up $500 the next year.

There was a final piece of icing on the corporate cake, which was the top-of-the-range Daytona Super III (below). Claiming 115 horses (86kW) it was a 900 triple running high 12:1 compression and tuning by Cosworth.

Up front you got six-piston brake calipers by Alcon, while several of the body panels and the muffler-wraps were carbon fibre. The price? A jaw-dropping $19,990 plus ORC at launch in 1994, which was bumped up by a grand the following year. Just 805 were made.

Modular mayhem

You have to admit, the whole modular idea enabled Triumph to pull off a surprisingly big range of motorcycles, despite the fact it ended up using two engines. In fact, the 900 triple accounted for eight models!

And it paid to get your head around the details, if you were ever to understand what you were buying. For example, the 900s could have any one of three basic front brake packages, featuring two, four or six pistons per caliper.

Mechanically, the series is generally tough with a reputation for hitting the 200,000km mark without much fuss, particularly if you keep up the oil changes. Synthetic oils were advised.

The one major issue to hit the T300 powerplants was failing starter (or sprag) clutches. Initial diagnosis indicated the early Sagem ECU set-up was at fault, which tried to fire before the starter had a chance to get the engine spinning at the right speed, which meant it sometimes kicked back. The sprag clutch itself eventually came under suspicion as well and was updated.

Many bikes were fixed under warranty and this was often an expensive job – we’re talking a couple of grand. Really, anything that’s still going should be okay. A tip, though: keep the battery well-charged (get a lithium unit) and follow the correct starting procedure, which is no throttle.

Prices on these early revival models have been flat for a long time and really you have to judge each example on its own merits. The really weird thing with this range is the model doesn’t seem to make a huge difference on price. Nearly everything costs Au$5000-8000 depending on condition.

The one exception is the Super III, and they don’t appear for sale very often. A good one here will be low to mid teens, though I’ve seen rough ones overseas for half that.

What to buy? The bikes I see gaining over the long term are:

Speed Triple, because it looks the goods;

Tiger 900 (good luck finding a clean and original one) because there’s a lot of affection out there in adventure tourer land for the ‘Steamer’;

Daytona Super III, because of its rarity and status as the premium model;

Daytona 1000, because of its relative rarity;

Daytona 1200, because it was the most powerful and fastest four-cylinder motorcycle Triumph ever made.

There’s a chance none of them will make you rich, but these things have that carved out-of-billet feel about them. They’re tough, were very well finished for their time and represent a critical stage in the company’s history.

Triumph along the way made a lot of people very happy with these things. As the owner of two examples, I can vouch for the fact that remains the case, some 25 years after they were made…

***

Our two Daytonas

Though I’ve owned others, the two remaining Hinckley T300s in my shed are a Daytona 1200 plus a Super III.

They’re essentially the same motorcycle, except for the carbon fibre dripping off the Super III and the extra cylinder on the 1200.

While Triumph only mentioned the Cosworth magic wand in relation to the Super III, there’s good reason to believe the 1200 got the same treatment, given it’s running the same high compression ratio and what feels like very similar tuning.

However the extra cubes means the 1200 has a top speed in the region of 270km/h, while the triple’s is more like 240-250.

Both feel top heavy, and the extra weight of the 1200’s powerplant is noticeable. Most people prefer the triple for its better-balanced feel.

The reach to the handlebars is long and rangy, while the fairing offers a remarkable amount of neck-to-ankle coverage.

Engine feel is quite different – the triple has that unique character, while the 1200 displays more brute force.

Both bikes responded well to some careful carburettor tuning, done by Charlie at Turn One Motorcycles in Melbourne. He’s a former Mikuni mechanic and has his own special ‘recipe’ for these things.

Suspension was actually pretty good on both, with quite a lot tuning available on the earlier versions. However, 25-ish years down the track, they will feel dated and tired. Pretty much any example will benefit from a professional rebuild and upgrade in this area.

They’re the sort of motorcycle that needs to be ridden with confidence to get the best out of them. Do that, and you’ll be surprised at how quick they are.

The Super III came with the Alcon six-spotter front brake calipers as standard, while you could order them as an accessory for the 1200 – which I did. They were among the best front brakes in the market back in the mid-nineties and still feel sharp and powerful today. The standard four-spotters on the 1200 are okay for their time, but not in the same class.

Though not to everyone’s taste, I have a real affection for the Triumph T300s. A lot of other motorcycles in the shed will go before they do and, weirdly enough, it's the 1200 that really does it for me as a ride…

Further reading

Hinckley Triumphs – the first generation

by David Clarke and published by Crowood – at Booktopia

See the feature on our Super III

See the Classic Two Wheels 1994 test on the Speed Triple

Triumph T300 series

Good

Tough and well-finished

Cheap

Not so good

Can feel tall and top-heavy

SPECS:

1993 Triumph Trident 900

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, four-valves-per-cylinder, inline triple

CAPACITY: 885cc

BORE & STROKE: 76 x 65mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 10.6:1

FUEL SYSTEM: 36mm Mikuni CV carburettors

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Steel spine frame with twin downtubes

FRONT SUSPENSION: 43mm fork with 150mm travel

REAR SUSPENSION: Preload-adjustable monoshock with 120mm travel

FRONT BRAKE: 296mm discs with two-piston calipers

REAR BRAKE: 255mm disc with two-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

WET WEIGHT: 235kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 775mm

WHEELBASE: 1534mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 25lt

TYRES:

FRONT: 120/70-17

REAR: 160/60-18

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 73kW

@ 9000rpm

TORQUE: 83Nm @ 6500rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE: $13,400 plus ORC

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact