Motorcycle Investor mag

Subscribe to our free email news

Profile – Suzuki RGV250 series

by Guy 'Guido' Allen, pics by Suzuki via suzukicycles.org & Suzuki UK

(August 2020)

Ready Racer

Suzuki’s RGV250 really was a racer with lights

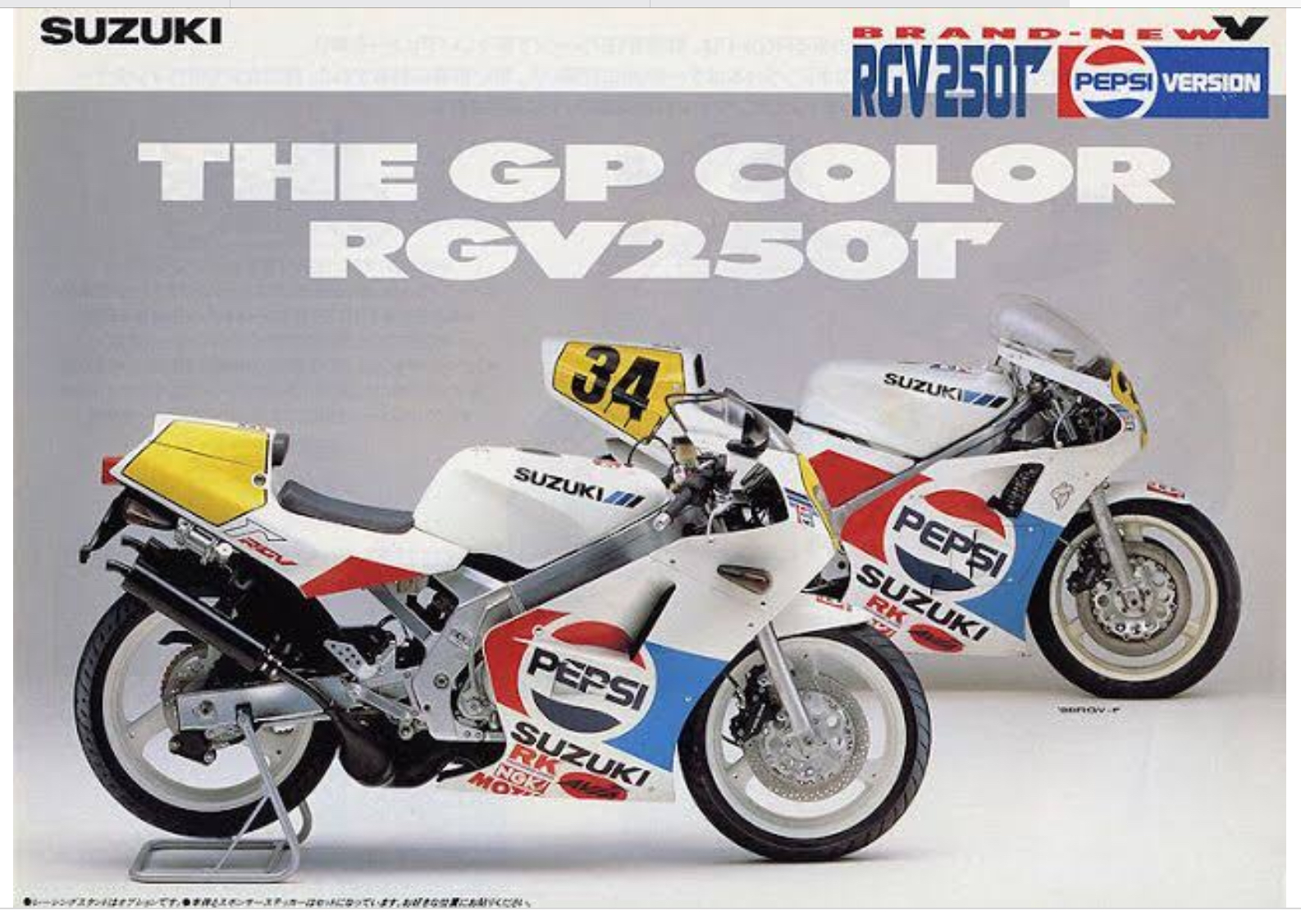

When in 1988 Suzuki first toddled into the market with its updated 250 two-stroke (top pic), it probably didn’t get quite the attention it deserved. The company had been producing ultra-quick parallel twin RG250s for some years by that point and so, while the V-twin update was interesting, it didn’t seem earth-shattering.

In fact it was. This was a motorcycle used for launching the race careers of pretty much every big name road racer across the western world for the next decade. You didn’t get a seat at the table with the big boys until you’d done your time on a 250 proddie, And the RGV was the mainstay of what turned out to be one of the most fiercely fought forms of road racing, ever.

In its heyday – even with the motorcycle industry in a

slump – a full field of 250 production bikes meant 30-40

young and hungry lunatics gridding up. The competition was

so close that skipping lunch could be regarded as an

unfair weight advantage.

Suzuki’s switch from a parallel to V-twin for this generation reflected was meant to reflect what had happened in grand prix, with Kevin Schwantz becoming the most prominent exponent of the company’s RGV500 V-four.

And while the company did make the race connection, there was something to back it up. Sure there was no 500 version, but the diminutive 250 was light, powerful, and a serious sports motorcycle. You did in fact have to wring its little neck to get the best out of it, but when you did the rewards were spectacular. Ridden well, it would give a 750 four-stroke a terrible fright.

Producing 59 horses (in full power form) at 11,000rpm, the little monsters didn’t really wake up until you got the tacho floating in the region of 8000rpm. Sure, they had powervalves, which effectively changed the shape of the exhaust chambers to provide something resembling lower and middle range urge. That meant they could be ridden on the street without the throttle constantly nailed, but they were relatively uninspiring as commuters.

Now that 59 horses may not seem like a lot, but it was tied to a dry weight claiming to be 129 kilos, so the power to weight ratio was excellent. Holding it all together was a generously proportioned aluminium frame, with a stocky swingarm and surprisingly good suspension at both ends And they had decent brakes.

What all that meant was, while you may not have had sheer brute force on your side, you did have the potential for serious handling finesse. These things could be thrown at a corner at speeds few other contemporary bikes would tolerate and come out the other side. Really that was the key to success with an RGV on the track – don’t back off for corners. And here’s a little stat to bring that into focus: the RGV series claimed a max lean angle of 58 degrees. Go on, try it at home…

There were two major revisions of the model over its lifetime: the M (above) of 1991 with its revised chassis and the P with its revised engine.

Let’s start with the M. This really marks the most

desirable update of the lot. Visually the bike looked more

like a serious GP toy, with the new upside-down fork up

front and huge banana-shape rear swingarm. The latter

really was a work of art.

There were countless other upgrades along the way, including a beefier frame and engine tweaks. The result was a much heavier weight claim at 139kg and a slight lift in power to 63 horses. While that may seem like a step backwards in power-to-weight, it was in reality a significant advance.

The chassis dynamics had been upgraded to qualify this as a new generation machine, with noticeably more robust handling. You could push it harder without ending up in the trees.

Sadly the banana swingarm was then replaced with a less visually pleasing girder design in 1993. It was just as effective, and the RGV continued to receive chassis and engine updates as it developed.

The biggest engine update was a change to a 70 degree (from 90) Vee with the P model (above) in 1993. Numerous internals were updated as part of this, plus there were some transmission upgrades. From the saddle, the alterations weren’t as big as you might expect and the power claims remained identical.

Suzuki’s ultimate throw of the dice for the RGV was the electric start VJ23SP (above) of 1997, claiming 70 horses. We didn’t get to see that one here, but new versions of the T series were sold here until 2000.

When it comes to service life, all two-stroke 250s of the era tended to be a little on the delicate side, though the RGV was stronger than most. The fact is they had to be worked hard to get the best out of them and no two-stroke of this nature is designed to have the sort of service life enjoyed by a big modern four-stroke.

The things that consistently hurt them was an owner using poor quality oil in it and using the bike for commuting. Powervalves could eventually break down and bits get fed to the engine, with inevitably catastrophic results. This is one of those rare cases where you might be better off with an ex-race bike, where the powervalves did less work and were fed good quality oil!

These things sold in very solid numbers priced at a little over $6000 (plus ORC) at first and ended up at more like $9200 towards the end.

Without exception, they were an engaging ride. Comfort was terrible, as we're talking a race bike with lights, though it did improve over the model life. But really a sore butt and wrists were the last thing on your mind if you could get one near a set of curves.

The handling was exceptional across the series – I really don’t believe they produced a dud – and became a little more sophisticated over time. You got the weird cackle from the engine and the mad surge of power as it hit the powerband – riding one of these things at speed was a very addictive experience.

I got to play with several models across the series and always walked away with mixed feelings: filled with adrenaline after what seemed like a death-defying ride, and somehow quite content to hand back the keys! Looking back, they were among the most exciting motorcycles I’d ever ridden, regardless of engine capacity.

Buying one these days represents a bit of a challenge for

two reasons: the people who own them tend to hoard them

and never stop at one; And the survival rate isn’t great.

This is an example where joining a two-stroke club would

be well worth your while, if you’re serious about getting

one.

Prices are all over the place. I recently saw a premium Schwantz replica being advertised at mid teens, while other clean examples of an M have popped up for closer to $10k. Half that might get a workable project bike.

If you do manage to get your hands on one, you’ll be

getting hold of a truly great play-racer. Enjoy…

***

Schwantz on braking

My favourite Kevin Schwantz quote goes back to when he was

doing fierce battle with the likes of Wayne Rainey, and

his Suzuki was a little light on top speed when compared

with his rivals. To make up for it, he became notorious

for desperate late-braking maneuvers. When asked about his

technique he quipped he would “see God, then brake.”

Another life

Suzuki’s RGV powerplant also powered Aprilia’s RS250,

which was sold here from 1998 to 2004. Aprilia applied its

own tuning to the engine and developed a very successful

competitor to Suzuki’s product.

Good

Fast

Exciting

Bad

Fragile

SPECS:

1991 Suzuki RGV250 M

ENGINE:

TYPE: Liquid-cooled, two-stroke 90-degree V-twin

CAPACITY: 249cc

BORE & STROKE: 56 x 50.7mm

COMPRESSION RATIO: 7.3:1

FUEL SYSTEM: Mikuni VM34SS x 2

TRANSMISSION:

TYPE: Six-speed, constant-mesh,

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

CHASSIS & RUNNING GEAR:

FRAME TYPE: Twin spar aluminium

FRONT SUSPENSION: USD telescopic fork fully adjustable,

120mm travel

REAR SUSPENSION: Monoshock fully adjustable, 140mm travel

FRONT BRAKE: 300mm discs with 4-piston caliper

REAR BRAKE: 210mm disc with 1-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS & CAPACITIES:

DRY WEIGHT: 139kg

SEAT HEIGHT: 755mm

WHEELBASE: 1375mm

FUEL CAPACITY: 17lt

TYRES:

FRONT: 110/70-17

REAR: 140/60-18

PERFORMANCE:

POWER: 47kW @ 11,000rpm

TORQUE: 40Nm @ 8000rpm

OTHER STUFF:

PRICE: $7750 plus ORC

-------------------------------------------------

Produced by AllMoto abn 61 400 694 722

Privacy: we do not collect cookies or any other data.

Archives

Contact